Jamshid Sharipov,

Jamshid Sharipov,

Head of Department of the Development Strategy Center

Today, Uzbekistan is experiencing a period of rapid urbanization, which is largely reflected in the country's capital, which concentrates key administrative structures, leading universities, as well as industrial and cultural centres.

This situation naturally turns Tashkent into a ‘magnet’ for internal migration, which intensifies demographic pressure and causes rapid growth in demand for housing, transport, energy, and utilities. However, the infrastructure often does not keep up with the population growth rate.

International organizations in their recent studies emphasize that cities with similar imbalances are facing chronic traffic jams, energy failures, environmental degradation, and a decline in the quality of life. At the same time, World Bank experts in the report ‘Thriving: Making Cities Green, Resilient, and Inclusive in a Changing Climate’ note that without innovation and investment, cities cannot meet the sustainable development standards[1].

The State of Urban Development in Uzbekistan

The trend towards urbanisation continues in Uzbekistan: by 1 July 2025, more than 19.3 million people (about 51% of the population) will live in cities, while 18.6 million will remain in rural areas, reflecting steady growing and continuing population outflow from rural areas. Tashkent has an official population of 3.1 million, but when migrants and students are taken into account, the actual number of people in the city on a daily basis may exceed this figure by 30-35%. This puts a huge strain on the road and transport system, energy sector and utilities.

In this case, special attention should be paid to educational infrastructure, as 98 of the country's 222 universities are concentrated in Tashkent. This uneven distribution has led to a massive influx of young people into the capital, exacerbating the problem of overloading housing, transport and urban services.

Another factor is the active construction of high-rise buildings without adequate analysis of the load on existing water, electricity and gas supply networks, which leads to frequent interruptions in utility services, especially during periods of peak consumption.

Key problems of urban development

Transport. Traffic jams have become one of Tashkent's most pressing problems.

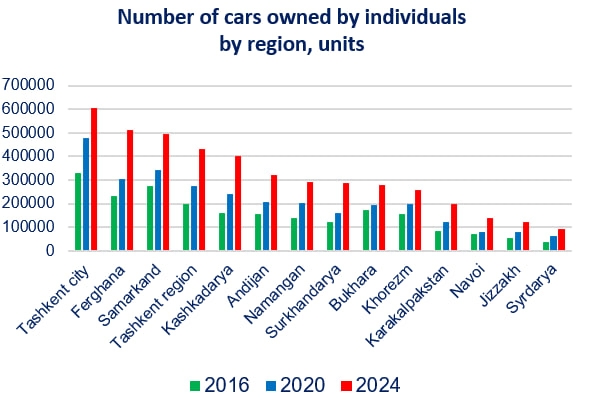

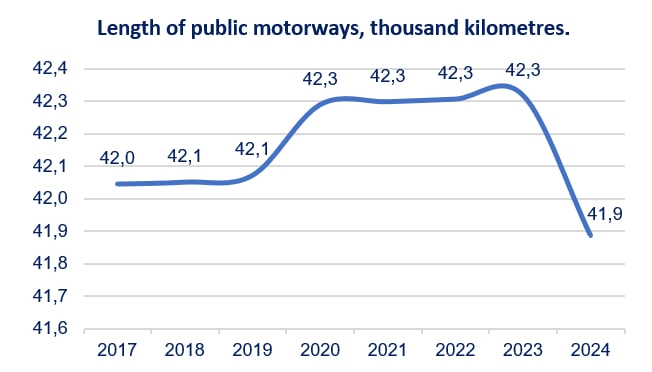

The average travel time during peak hours exceeds 50-60 minutes. Over the past eight years, the number of cars has almost doubled, while the length of the road network has decreased by 0.5%[2]. This, in turn, creates an imbalance and leads to chronic congestion of highways. Additionally, the situation is complicated by the shortage of parking spaces, the weak development of public transport, and the lack of integrated solutions for the ‘last mile’.

According to UN estimates, by 2040, almost 60% of the world's population will live in cities, while the number of trucks, passenger cars, and air transportation will double, and the volume of emissions will continue to grow. As a result, millions of people die in road traffic accidents both directly (as a result of accidents) and indirectly – due to emissions.

The World Bank, in its report ‘Promoting Liveable Cities by Investing in Urban Mobility’, emphasizes that the increase in the use of personal vehicles leads to a rise in traffic jams, air pollution, and a decrease in the availability of jobs and social services[3].

Energy. The problem of energy supply remains one of the most serious. According to a study conducted by the Prosecutor General's Office[4] in the summer of 2025, more than 2,540 km (26%) of electrical networks in Tashkent are in an advanced state of disrepair, and some substations require modernization or capacity extension. In addition, the shortage of emergency teams, outdated equipment, and high staff turnover are exacerbating the situation: in just the last three years, about 30% of employees, including specialists from operation and repair services, have left the system. This leads to interruptions in electricity supply and a decrease in the stability of urban infrastructure during peak consumption periods.

Energy. The problem of energy supply remains one of the most serious. According to a study conducted by the Prosecutor General's Office[4] in the summer of 2025, more than 2,540 km (26%) of electrical networks in Tashkent are in an advanced state of disrepair, and some substations require modernization or capacity extension. In addition, the shortage of emergency teams, outdated equipment, and high staff turnover are exacerbating the situation: in just the last three years, about 30% of employees, including specialists from operation and repair services, have left the system. This leads to interruptions in electricity supply and a decrease in the stability of urban infrastructure during peak consumption periods.

The Asian Development Bank, in its report ‘Harnessing Uzbekistan's Potential of Urbanization: National Urban Assessment’, notes that Uzbek cities are already experiencing infrastructure shortages, climate and environmental risks, and lack of quality urban services, especially in less large and medium-sized cities - similar to the problems observed in Tashkent.[5].

Ecology. The ecological situation in Tashkent is deteriorating year by year. The average annual concentration of PM 2.5 in the city exceeds the WHO average by more than six times. At the same time, the main sources of pollution are the heat supply system (≈28%), transport (≈16%), industry (≈13%) and transboundary wind-blown emissions (≈36%), which prevail in summer[6].

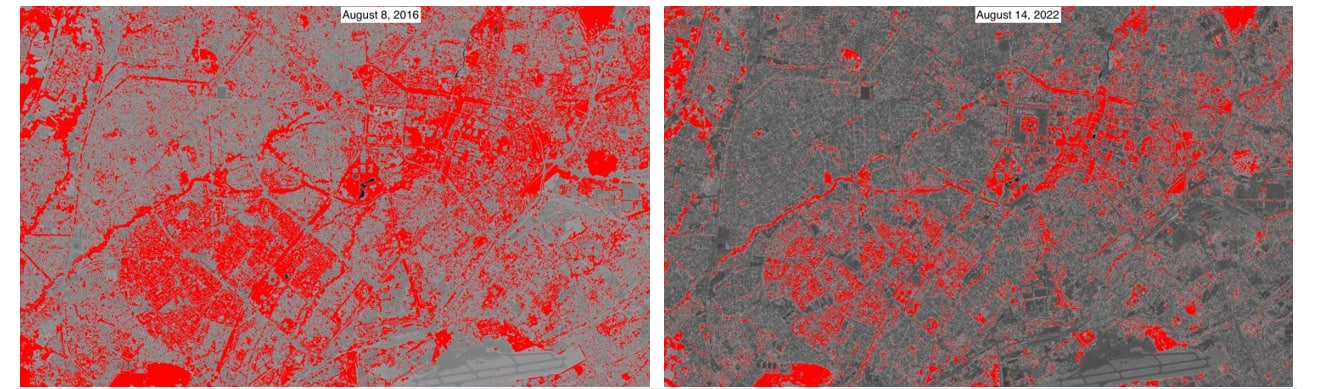

It should be noted that uncontrolled housing construction and the reduction of green areas also reduce the city's ability to cope with dust and thermal islands. According to NDVI satellite images (standardized index of differences in vegetation cover), in just six years, vegetation in the city has decreased from 34.6% to 13.1%[7]. At the same time, according to international standards, the minimum norm of green spaces in the city should be at least 25% of the territory or 9 sq. m of green zones per resident[8].

NDVI index of Tashkent city

According to UN-Habitat’s ‘World Cities Report 2024: Cities and Climate Action’ report, cities not only suffer from climate change but are significant sources of emissions and environmental risks themselves, especially where infrastructure development lags behind population growth and transport load[9].

Water supply. Water supply problems are becoming increasingly acute for the residents of Uzbekistan. According to experts, about 60% of city water supply networks are outdated, a significant part of the pipes has been in operation for more than 40-50 years, which leads to frequent accidents, leaks, and deterioration of water quality[10].

The World Bank report ‘Uzbekistan Infrastructure Governance Assessment’ emphasises that a significant portion of water is lost due to leaks, illegal connections, and a weak metering system. A lack of funds for network maintenance and renewal increases the risk of accidents and reduces service quality. Problems with non-revenue water (leaks, low pressure, poor management) further undermine the sustainability of water supply systems. All of this together reduces the availability of basic public services and creates risks to public health[11].

Waste Management. The system of solid household waste management remains insufficiently developed. According to official data, in 2024, the volume of solid household, liquid, and construction waste continued to grow, which requires expanding capacities for their collection, utilization, and processing, the share of plastic in the composition of waste is approaching 10%, however, the capacities of processing enterprises remain limited.

In 2024, the country generated 14.8 million tonnes of household waste, of which only 900,500 tonnes, or 6.1%, was recycled. A quarter of household waste consists of paper, plastic, rubber, glass and textile residues. At the same time, only 18% of waste is recycled in Tashkent, with an annual volume of 700,000 tonnes. The level of separate waste collection also remains extremely low, which reduces recycling opportunities and increases the burden on landfills.

Recommendations for solving urban development problems based on foreign experience

Based on an analysis of current urban development issues, and in order to ensure the full implementation of the goals of the Uzbekistan-2030 Strategy for comprehensive development of regions and increasing the level of urbanisation from 51 per cent to 60 per cent, an expert of the Development Strategy Centre proposes a set of innovative measures that have proven effective in leading cities around the world and can be adapted to the conditions of large cities in Uzbekistan. These recommendations provide systemic solutions that integrate digital technologies, decentralised management models and green practices, ensuring the sustainability of the urban environment.

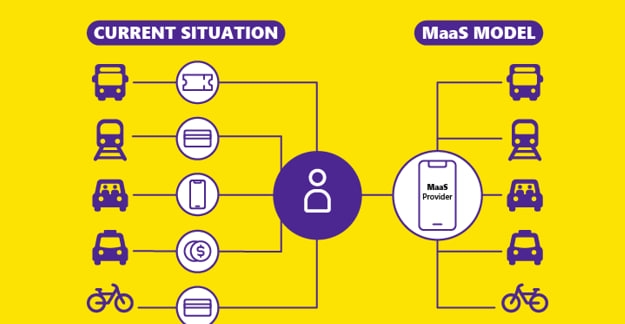

Transport. The problem of chronic traffic jams in Tashkent can be solved by introducing the concept of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). Such a system is already operating successfully in Helsinki, where the integration of the metro, buses, taxis, car sharing and bicycles into a single digital platform has reduced the use of private cars by 12% in just two years[12].

Transport. The problem of chronic traffic jams in Tashkent can be solved by introducing the concept of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). Such a system is already operating successfully in Helsinki, where the integration of the metro, buses, taxis, car sharing and bicycles into a single digital platform has reduced the use of private cars by 12% in just two years[12].

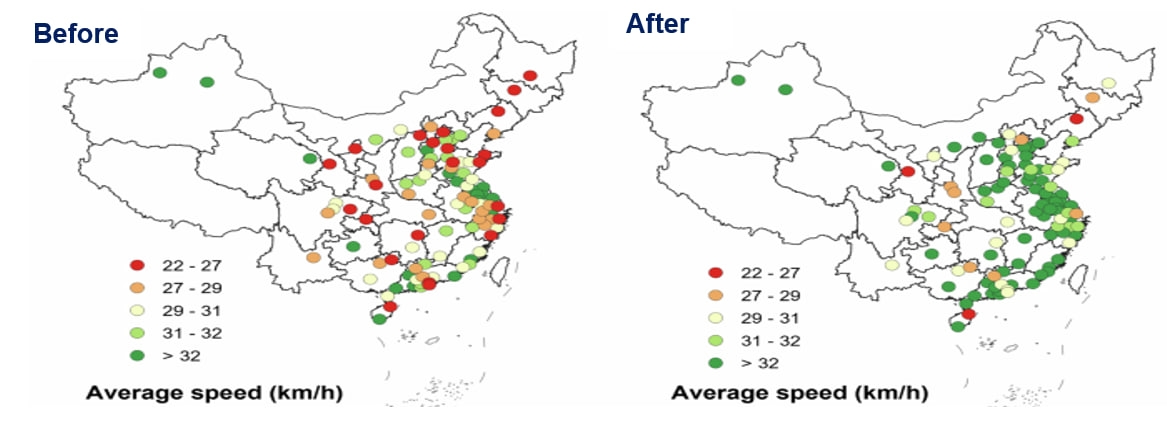

Another area of focus is the use of intelligent traffic management systems, including real-time traffic monitoring and forecasting, intelligent traffic light control, predictive traffic management using AI, and intelligent parking solutions. In densely populated Chinese cities such as Shanghai, the introduction of AI-based traffic management technologies has reduced traffic congestion by 18% and cut average journey times by 9 minutes[13].

Changes in traffic speed during peak hours in Shanghai

(before and after introduction of traffic management technologies based on II)

Adapting similar solutions for Tashkent will reduce road congestion by 20-25% by 2030 and reduce average travel time during peak hours from the current 60 minutes to 45 minutes.

Adapting similar solutions for Tashkent will reduce road congestion by 20-25% by 2030 and reduce average travel time during peak hours from the current 60 minutes to 45 minutes.

Energy. To increase the stability of energy supply in cities, it is advisable to consider the possibility of using decentralized solutions such as virtual power plants (VPP) and local microgrids

In Germany, the Next Power Plant project has united about 15 thousand small energy sources into a single network, which has increased the stability of energy supply[14]. The uniqueness of VPP Next Kraftwerke is that, by combining the capacity of installations, VPP can provide the same services and accumulate, and then trade in the same markets as large central power plants or industrial consumers.

The main feature of the VPP is the stabilization of the network during peak demand and the provision of electricity during disruptions. VPP participants can benefit from financial incentives, while the network becomes more reliable and can integrate more renewable energy sources.

In the United States, in the neighbourhood of Brooklyn, a pilot microgrid has enabled residents to exchange energy directly via the Brooklyn Microgrid blockchain platform[15].

In Tashkent, such technologies can reduce power outages by 30% and ensure up to 15% energy savings through decentralised generation and load optimisation.

Ecology. The introduction of the ‘digital twin city’ can be a promising tool for improving the environmental situation. This approach allows modelling transport, energy, and environmental processes by assessing the consequences of various development scenarios.

A striking example is the Virtual Singapore project, where government agencies use a digital model to develop policies, companies and start-ups use it to create applications in the field of urban services and ecology, and researchers use it to analyse the impact of the urban environment on public health and climate processes[16].

For Tashkent, the introduction of a similar platform could form the basis for more rational urban planning, monitoring of green areas and air quality management. The use of a ‘digital twin’ will enable effective forecasting of heat islands, identification of optimal locations for greening and control of pollution levels. According to preliminary estimates, this could increase the area of green spaces by 15% by 2030, as well as reduce the impact of heat islands and PM 2.5 concentrations by 10–12% through more accurate planning and integration of green technologies.

Water supply. To solve the problems of outdated water supply networks and high water losses, Tashkent needs to switch to smart management systems. International experience shows that such solutions are highly effective. In South Korea, the introduction of the Smart Water Management system in the city of Sosan has reduced water leaks by 21% and emergency situations by 15% thanks to the installation of pressure sensors and digital monitoring[17].

In Israel, a centralised water supply monitoring and management system ensures one of the lowest rates of non-revenue water in the world. In the 2020 rankings, Mekorot Water Company was recognised as one of the best utility companies in the world thanks to its water loss rate of less than 3%, compared to the OECD average of 15%[18].

In Syracuse (USA), the use of predictive analytics and Big Data algorithms has made it possible to predict the wearing out of water pipes and identify areas where accidents are most likely to occur. Instead of merely responding to accidents, this method has enabled the city of Syracuse to carry out preventive repairs, reducing the number of pipe breaks and lowering emergency repair costs[19].

Adapting such solutions in Tashkent will improve the efficiency of water supply networks, reduce leaks by 15–20%, cut the number of accidents by 15% and ensure even water distribution in new residential areas.

Waste management. To improve waste management efficiency, it is necessary to develop modern processing facilities and introduce a separate waste collection system. The Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) has set a goal to transform Seoul into a ‘Zero Waste’ city by 2030 by adopting a ‘Waste Management Action Plan’ to reduce waste generation at source and promote the recycling of waste into resources. As a pilot project, 112 waste recycling stations were set up in five districts of Seoul, where residents sort recyclable materials themselves. As a result, the amount of household waste has been reduced by more than 20%, and the amount of recyclable materials collected has increased thanks to growing participation levels[20].

In Stockholm, a significant portion of household waste is converted into heat and electricity, which provides about 20% of the city’s heating needs (Stockholm Exergi). The company’s experts emphasise that landfilling waste is the least effective and most dangerous way to dispose of it for three key reasons.

Firstly, when organic materials decompose in landfills, methane is released — a greenhouse gas that is 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Secondly, waste contains heavy metals and other toxic substances that can contaminate groundwater and water bodies if they leak. Thirdly, landfill deprives waste of its potential: it is not used either as secondary raw material or as a source of energy[21].

For Tashkent, the introduction of such practices could increase the waste recycling rate from the current 6–10% to 35–40% by 2030, reduce the burden on landfills and cut methane emissions.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the problem of urban development is systemic in nature and affects transport, energy, utilities, the environment, water supply and waste management. However, international experience shows that with the competent adaptation of innovative solutions, it is possible to reach a new level of sustainability. The MaaS concept and AI transport management can reduce traffic jams, virtual power plants and local microgrids will strengthen the energy system, digitalisation and intelligent management of utility networks will reduce accidents, resource losses and ensure stable access, while robotic waste sorting and digital twins of cities will help improve the environmental situation and expand green areas.

[3] https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/03/13/promoting-livable-cities-by-investing-in-urban-mobility?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[4] https://uza.uz/uz/posts/toshkent-shahrida-elektr-taminotidagi-uzilishlar-sabablari-organildi_743267

[10] https://www.tashkenttimes.uz/national/8988-uzbekistan-could-slip-to-water-scarcity-red-zone-by-2050?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[11] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/9a1b20251d1688c58b83ce8d3baa250f-0080012023/original/Uzbekistan-InfraGov-Report.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[14] https://www.next-kraftwerke.com/vpp